Peanut season is nearly upon South Carolina and, like governments across the country, the state has been scrambling to hire.

Its Department of Agriculture is lifting pay for crop inspectors to $13 to $16 an hour from the previous $9.50 to $11.50, and creating an “aide” version of the position that requires less education and experience. It is even tweaking the title to make it sound more appealing: what used to be “temporary inspector” is now a “peanut grading inspector.” All this in a bid to find the 125 people it needs to help ensure peanut safety during the September to November harvest.

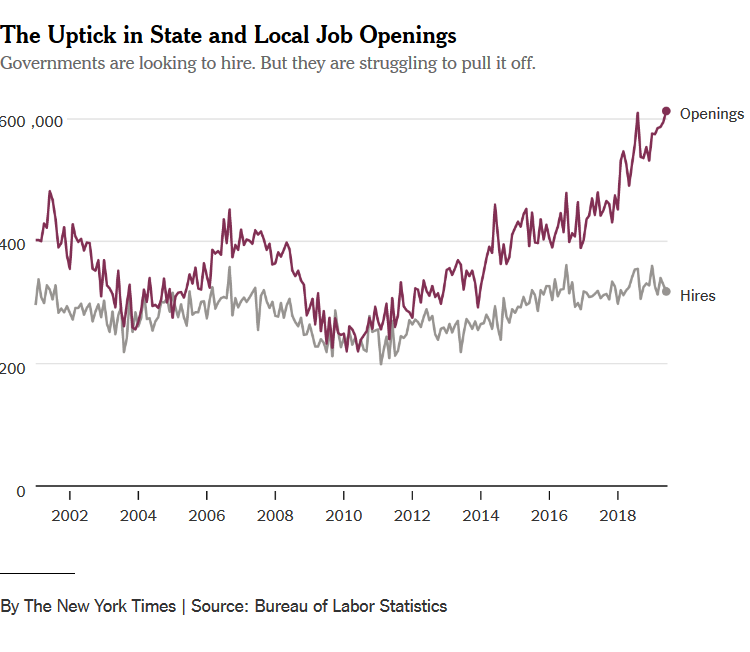

It is an example of what’s happening nationwide. Public agencies that perform crucial functions are struggling to compete as unemployment hovers near its lowest level in a half-century. The public sector has been posting record job openings, and state governments have lost about 20,000 employees since mid-2018, based on Bureau of Labor Statistics data.

The tight labor market is forcing both states and localities to take a second look at imperfect applicants, raise wages and even run short-staffed as they try to keep police departments, schools and state capitols functioning smoothly.

Public sector employers compete with the private sector for manpower, but often face more rigid budget constraints. As a result, they often pay less or raise wages more slowly; in fact, only a little more than half of state and local agencies think that they pay competitively, based on one recent survey. They can struggle to compete when labor markets are tight and workers have plentiful options.

“State and local governments are having to do a lot more with a lot less,” said Dan White, director of fiscal policy research at Moody’s Analytics. He noted that the public sector has been cautious in hiring for years as mandatory spending on health care and pensions sucks up their budgets. The hot labor market is making matters worse. “There’s a lot more opportunity for advancement and higher pay in the private sector.”

In addition, states are rebuilding workforces that took a major hit during and after the Great Recession and now face a wave of retirements delayed by the downturn. The result is widespread employee shortages. There were two public-sector job openings for every new hire in June, a sign that state, local and federal agencies are struggling to quickly fill positions.

That is up from 1.7 a year earlier, and much higher than the private-sector ratio, which is 1.2.

In South Carolina, “last season was the worst season we’ve ever had,” said Dave Baer, human resources manager at South Carolina’s Department of Agriculture and the person in charge of hiring peanut inspectors.

The state turned to contractors in 2018 after failing to attract enough laborers, a trend across governments as they look for more flexible staffing. It resulted in fraud and inefficiencies, so Mr. Baer got raises approved this year, which helped him find enough new workers to satisfy the state’s needs.

“We knew it was going to be a struggle to compete,” he said.

For people like Cynthia Cuffie, 62, the more aggressive push to hire has created opportunities.

Ms. Cuffie has not worked formally in years. The Hartsville, S.C., resident lives in a house her mother left her and helps take care of her sister, who in turn pays for Ms. Cuffie’s basic living expenses. But peanut inspecting could allow her to better maintain her beloved truck, a 1997 Toyota T-100 given to her by a relative. When she saw the peanut-inspector job advertised on Facebook, she knew she ought to try for it.

“It’s going to do marvels for me,” said Ms. Cuffie, who landed the gig and began training on Aug. 20. She is planning to repay her sister for new tires she has just bought, and then pay tithes at her church. “It’s going to get me out of the hole.”

In Washington State, a shortage of information technology and health care workers has prompted it to compete with the private sector despite budgetary constraints, said Franklin Plaistowe, assistant director of the state’s human resources division. To attract workers, it touts its public service-oriented mission, as well as good benefits and unique perks: Some employees can now bring their infants to the office.

“We’ve had four babies come through and retire,” Mr. Plaistowe said of his own department. “We’re thinking, from a human perspective, of our employees, and how we can meet them where they are.”

Gerald Young, a researcher at the nonprofit Center for State and Local Government Excellence, said he has seen governments in Iowa share health care personnel across county lines, and school districts in Nebraska allow science and math teachers to return from retirement to fill workplace gaps.

There are unique risks in public employee shortages. Police departments, prisons and state hospitals provide essential services, so society can pay the price when those jobs go unfilled.

About 32 percent of local governments report difficulty filling policing jobs, 29 percent are struggling to find engineers and 24 percent are searching for laborers and skilled tradesmen, the survey found. And states are finding it’s hardest to find office, information technology and accounting workers.

It is tough for states to be more nimble in a hot labor market. Nearly all have balanced-budget requirements, according to the Urban Institute, which means they cannot spend more money than they collect. Many have strict taxing and spending limits and use salary brackets that are slow to change. Pay for state and local public employees has grown more slowly than private-sector pay since the last recession, based on Bureau of Labor Statistics data.

Pay for many unionized public sector workers has improved in recent years against the strong economic backdrop, according to Steven Kreisberg, research director at the American Federation of State County & Municipal Employees. But some states are using higher tax revenue from a strong economy to cut taxes instead of hiring new public workers or paying more.

America’s prisons show what can happen when the public work force shrinks as a share of the population. Federal and state penitentiaries have been understaffed for years, because of structural problems — prison work can have a bad reputation — and policy choices, including a hiring freeze at federal prisons from 2017 to early this year. The hot job market is exacerbating the problem.

In Wisconsin, overtime payments increased by $7.5 million between 2016 and the 2018 fiscal year as the state correction system struggled to fill jobs. Colorado and Texas are also plagued by shortages and high overtime.

“There were always concerns about the competitiveness of correctional jobs compared to law enforcement,” said Brian Jackson, a researcher at the RAND Corporation. “Then you add the hot labor market and there are a lot of other options, especially for people who have gone through training, and it becomes a human capital challenge.”

The question for state, local and even federal employers now is: What happens next?

The economy may be slowing, which could offer an unhappy reprieve. President Trump’s trade war has dragged on business investment and is beginning to put a dent in consumer confidence, and a global economic slowdown could eventually weigh on American output and employment growth.

For now, the job market has appeared unfazed. Unemployment stands at 3.7 percent and wages are climbing. While fissures may be forming — factory hiring has slowed and the share of Americans who are working or looking for work seems to have peaked — it’s too soon to tell if that will cause a broader slowdown.

That’s great news for people like Ms. Cuffie, the soon-to-be peanut inspector.

“I can’t wait to get the check,” Ms. Cuffie said. “So I can’t wait to do the work.”