Americans born after 1980 have been wrestling with sharp price increases for the first time since they've been old enough to notice. Millennials have spent much of their lives enduring economic calamity. Many were children when the dot-com bubble burst; graduated from high school in the late 2000s, when the real estate market crumbled; and had to compete with a huge generation of baby boomers in an anemic postcrisis job market before Covid-19 brought the global economy to its knees last year.

But there was one powerful phenomenon that millennials, the largest generation in the United States, had never felt, at least as adults: rapid inflation.

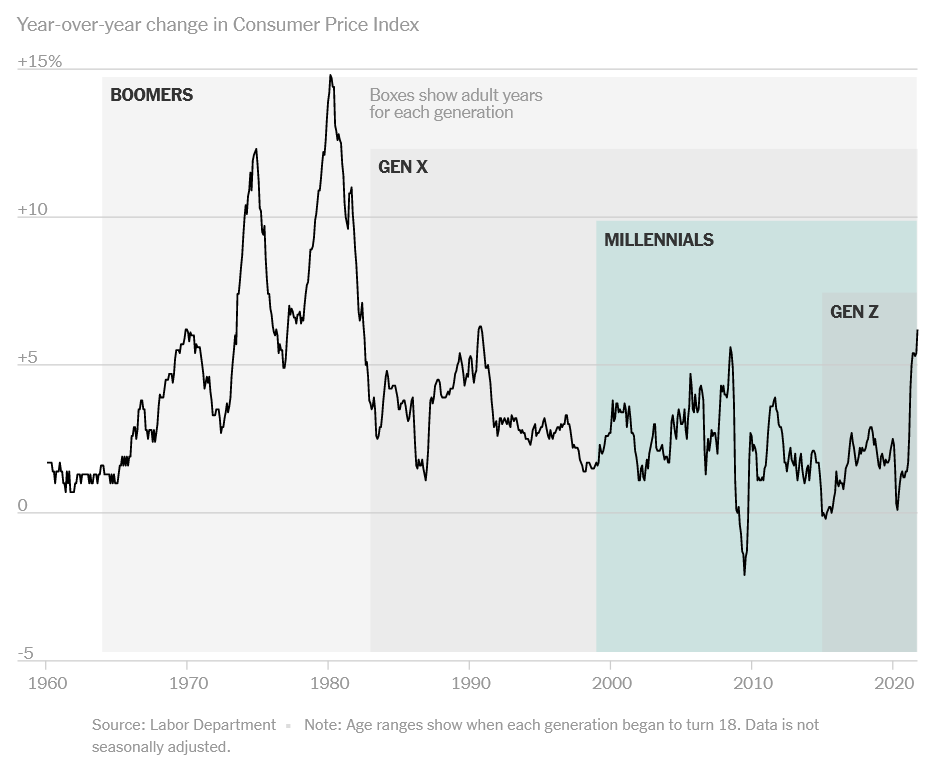

Americans born from 1981 to 1996 — along with the younger Generation Z — have been wrestling with sharp price increases for the first time since they’ve been old enough to notice. Growth in the Consumer Price Index, a primary measure of inflation, has been rising for months and is touching its highest level since 1991, when boomers (born from 1946 to 1964) were roughly the same age as millennials are now. The closest that inflation has come to that mark since then was in 2008, when soaring oil prices briefly pushed up the overall index.

Now, supply chain snarls, sky-high consumer demand for goods and worker shortages that are limiting production and lifting wages have pushed up the costs of furniture, cars, housing, food and other products. It’s hard to see when the turmoil might end.

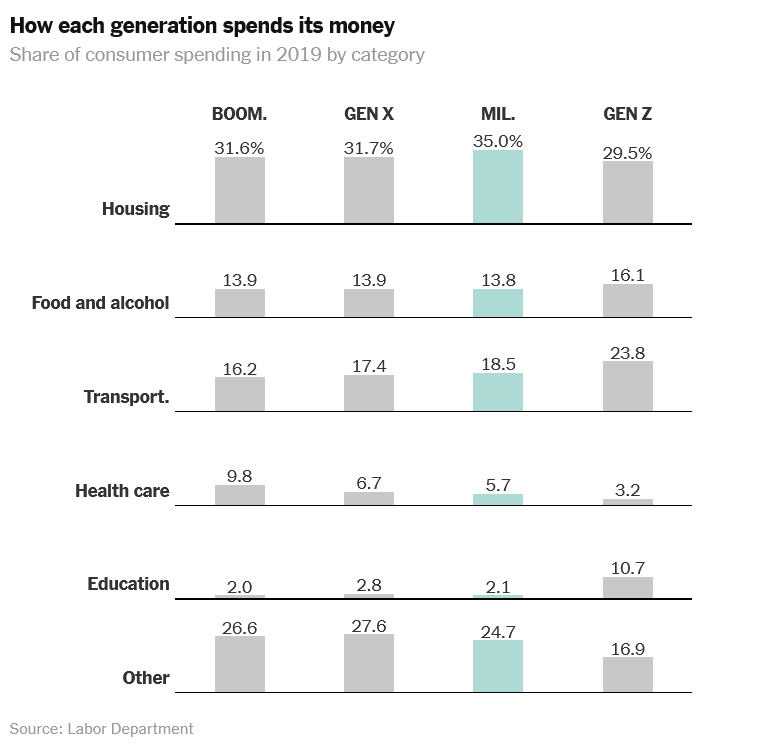

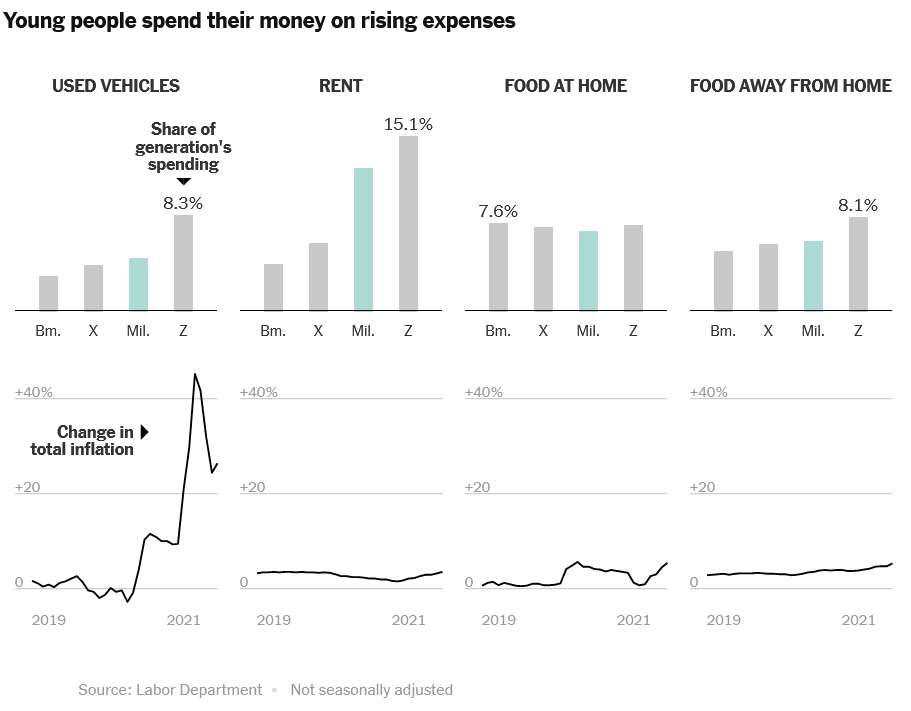

But the price increases have been felt unevenly. Some of the most extreme gains have come in categories where millennials and their younger counterparts are more likely to spend money than older generations, Labor Department data shows. Gasoline prices, something that policymakers can do little to control, are up nearly 50 percent this year — and Americans in their 20s and 30s spend more of their monthly budget on gas than other age groups, the data shows.

Younger people also tend to be renters, leaving them more exposed to rising rents than older generations, who are more likely to be homeowners. They often buy used cars, meaning they have borne the brunt of used-vehicle prices that are up 26 percent over the past year, according to the Labor Department. (Baby boomers are more likely to buy new cars, which have gone up in price but not as much.) And while people of all ages are being affected by higher food prices, young adults tend to dedicate more of their money to restaurant meals.

Ali Wolf, chief economist at Zonda, a housing data firm, said her millennial friends regularly talk about rising prices and goods shortages but don’t seem as frightened as older generations. Part of that, she thinks, may be because they don’t have memories of the last time when inflation was bad — unlike baby boomers, who were just entering the work force during the “Great Inflation” of the 1970s and early 1980s. (Members of Generation X mostly missed the Great Inflation but came of age during a period when inflation remained higher than in the 2000s.)

Many young adults have also saved money and paid down student loans during the pandemic, when they were stuck at home and, in some cases, receiving government relief checks. That may have put them in a better financial position to handle higher prices, at least for a while.

But not everyone is able to navigate the moment easily.

“One friend has a big family, she’s a millennial, and she said her grocery bill is impacting her ability to spend money elsewhere,” Ms. Wolf said.

Even within generations, rising prices don’t hit everyone the same way. Young parents like Ms. Wolf’s friend dedicate far more of their monthly budgets to groceries than people without children, and more than older parents, who tend to be more stable financially. Low-income families of all generations spend more on housing, gas and other essentials than wealthier families.

Then there are the smaller items that together can add up. Most Americans don’t go to a laundromat, for example, but those who do — a group that’s heavily skewed toward young people — spend hundreds of dollars a year there, and have seen their costs go up nearly 7 percent over the past year.

The good news for younger workers is that it isn’t just prices that are going up; pay is rising, too, especially for less-skilled workers and the very young. But for the typical worker between 25 and 34 years old, price increases have been outpacing wage gains in recent months.

The rapid inflation could have big policy implications. Officials at the Federal Reserve are closely monitoring outlooks for consumer prices. The worry is that if people begin to expect a faster pace of inflation, workers will demand higher pay to cover it — and employers will raise prices further to pay for those raises. That could set prices and wages on an upward spiral, making a short inflationary burst last longer.

People who lived through the Great Inflation tend to expect inflation to be higher in the future more than younger generations, surveys show. But price outlooks among Americans younger than 40 are beginning to climb, survey data from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York suggests. And confidence in the overall economy among younger people — who are usually the most optimistic age group — is wavering. In a widely cited sentiment survey from the University of Michigan, younger people have sharply lowered their expectations for purchasing conditions.

It’s a big change for them, since inflation had been on a downdrift since the 1980s.

“Well before millennials even came along, we’d been going through this period of declining interest rates, declining inflation, declining expectations,” said Neil Howe, the researcher of generations who coined the term “millennial.” Now that has been upended — at least temporarily, and maybe for a while.