Mild October prices report unleashes stock and bond rallies. Inflation’s broad slowdown extended through October, likely ending the Federal Reserve’s historic interest-rate increases and sparking big rallies on Wall Street.

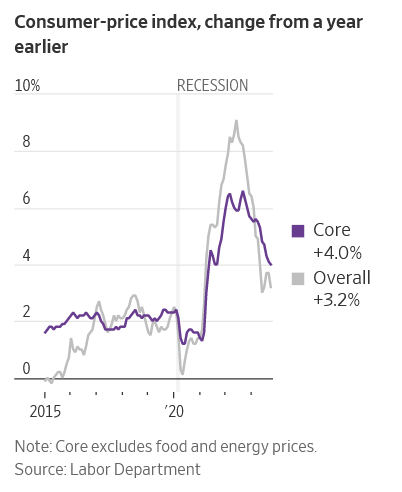

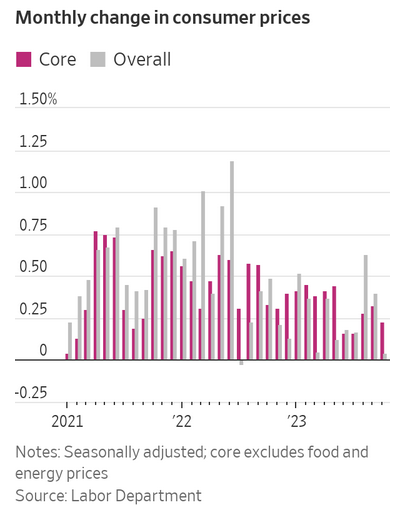

Consumer prices overall were flat last month and rose 3.2% from a year earlier, a slower pace than in September, the Labor Department said Tuesday. Overall inflation hit a recent peak of 9.1% in June 2022.

Increases in so-called core prices, which exclude volatile food and energy items, also showed underlying price pressures are abating. Core inflation for the five months ended in October was at an annual rate of 2.8%, down from 5.1% during the first five months of the year.

The easing reflected lower prices for cars and airfares and milder growth in the cost of housing and other services. Core inflation is often viewed as a better predictor of inflation’s future trajectory than the overall numbers.

“The hard part of the inflation fight now looks over,” said David Mericle, chief U.S. economist at Goldman Sachs.

Stocks and government bonds soared as investors concluded the Fed was done raising rates and shifted attention to when officials might begin cutting rates.

The Nasdaq closed up 2.4%, while the S&P 500 rose 1.9%, the biggest one-day jumps for both since April. The Dow Jones Industrial Average added nearly 500 points, or 1.4%.

Yields fell sharply across Treasurys, with the benchmark 10-year note declining 0.191 percentage point to 4.440% on Tuesday. That was the largest single-day decline since Silicon Valley Bank failed in March. Yields fall as bond prices rise.

Many Americans are taking little comfort from the inflation slowdown because the run-up in prices of everything from cars to groceries to housing since 2021 has been abnormally large.

With the October report, core prices have increased for five straight months more slowly than in the previous two years. That string of lower readings is moving closer to what Fed officials have long said would be necessary to convince them they no longer needed to raise rates.

The Fed has raised interest rates this year to a 22-year high to combat inflation by slowing economic activity. They last raised them in July. Since then, officials have extended a pause in rate increases and are very likely to do so again at their next meeting, Dec. 12-13.

When inflation first jumped in 2021, the Fed and most economists thought price increases were tied mostly to pandemic-driven disruptions and would largely fade on their own. Officials spun a U-turn at the end of 2021 when they concluded price pressures were being fueled by excessively strong demand, and they raised rates last year at the most rapid pace in four decades to combat inflation that also hit 40-year highs.

They slowed the pace of increases at the end of last year and lifted their benchmark rate at a more measured pace through July. By holding rates steady next month, the Fed would be extending its current pause to around six months.

That pause has coincided with a gradual slowdown in hiring and with strong consumer spending, fueling optimism that the central bank is for now achieving a so-called soft landing for the economy that brings inflation down without a big increase in joblessness.

Officials including Fed Chair Jerome Powell have been unwilling to declare victory over inflation by pointing to past instances when they thought price pressures were ebbing, only for them to turn around and march higher. Some officials are also cautious because of the risk inflation stalls out above the Fed’s 2% target, even if it continues to tick lower.

“Considering the scars left by the inflation spike, there’s little to be gained and much to lose by declaring the end of the tightening cycle,” said Daleep Singh, a former executive at the New York Fed who is now chief global economist at PGIM Fixed Income. ”But the reality is they are very likely done with rate hikes.”

Other Fed officials have touted recently significant progress watching inflation fall without a big increase in job losses. The 12-month inflation rate is on track this year to have posted its largest annual slowdown during peacetime.

“We may have brought down inflation as fast as it has ever come down, and we did that without starting a recession,” Chicago Fed President Austan Goolsbee in an interview last week.

Indeed, the October inflation report will cheer officials who had recently played down fears that robust consumer spending might sustain an interval of stubbornly high inflation. Those officials warned against overreacting to strong growth and have instead said the central bank policy decisions should be guided by how inflation behaves. “The primacy of inflation has to carry the day right now,” Goolsbee said.

Analysts said the latest data also reduces the prospect that the Fed will have to resume rate increases early next year. Rather than focus on whether to raise rates, the debate at officials’ next meeting could instead center on whether and how to modify the guidance in their postmeeting statement to reflect recent progress on inflation as well as the dimming prospect of further rate increases.

Whether the Fed can sustain this painless decline in inflation depends in part how the economy responds over the coming year to its past monetary tightening.

Strong consumer spending has helped power this year’s economic resilience, but economists forecast Americans will pull back as the impact of the Fed’s rate increases continues to permeate the economy. That includes an expected slowdown in jobs and wage growth, which could deflate Americans’ willingness to spend.

Tuesday’s inflation report was greeted with relief by several private-sector forecasters who had braced for a larger increase in core prices last month because of a calculation in healthcare costs that is incorporated every October. “This was a report we and others had been dreading for a few months,” Mericle said.

Not only was the latest data friendlier than anticipated, but several sources of cooling prices, including cars and housing, could continue to slow the rate of price increases in the months ahead, Mericle added.

Mid-America Apartment Communities, which has ownership in more than 100,000 apartment homes in 16 states and Washington, D.C., last month said it has been lowering rents to attract new tenants. A pandemic-era building boom is leading more apartments to hit the market when their developers are being squeezed by higher debt-financing costs than they anticipated.

While rents for existing tenants rose 5% in July through September, rents for new tenants fell 2.2% from a year earlier. One year ago, rents for new tenants were up 13.7% while renewals rose 14%.

“We knew in a high-supply environment that lease-up pressures exist, but I think it’s just been a little bit more intense because of what’s going on with the interest-rate environment,” Mid-America Chief Executive Eric Bolton said on an earnings call last month.

Write to Nick Timiraos at Nick.Timiraos@wsj.com and Amara Omeokwe at amara.omeokwe@wsj.com